Password Reset

Forgot your password? Enter the email address you used to create your account to initiate a password reset.

Forgot your password? Enter the email address you used to create your account to initiate a password reset.

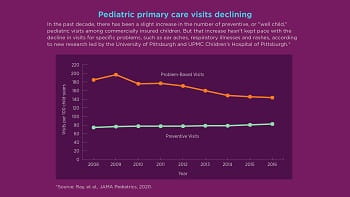

Commercially insured children in the U.S. are seeing pediatricians less often than they did a decade ago, according to a new analysis led by a pediatrician-scientist at the University of Pittsburgh and UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh.

But whether that’s good or bad is unclear, the researchers say in the study, published today in JAMA Pediatrics.

Kristin Ray, MD, MS, assistant professor of pediatrics, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, and pediatrician and director of health system improvements, UPMC Children’s Community Pediatrics

“There’s something big going on here that we need to be paying attention to,” said lead author Kristin Ray, MD, MS, assistant professor of pediatrics in Pitt’s School of Medicine. “The trend is likely a combination of both positive and negative changes. For example, if families avoid bringing their kids in because of worry about high co-pays and deductibles, that’s very concerning. But if this is the result of better preventive care keeping kids healthier or perhaps more physician offices providing advice over the phone to support parents caring for kids at home when they’ve got minor colds or stomach bugs, that’s a good thing.”

Ray and her colleagues examined insurance claims data from 2008 through 2016 for children 17-years-old and younger. The data came from a large commercial health plan that covers millions of children across all 50 states with a range of benefit options.

In that time span, primary care visits for any reason decreased by 14%.

Preventive care, or “well child” visits, increased by nearly 10%. This change occurred during the years when the Affordable Care Act eliminated co-pays for such visits. But that increase was eclipsed by a much larger decrease in problem-based visits for things such as illness or injury, with these visits declining by 24%. Among problem-based visits, decreases were seen for all types of diagnoses, except for psychiatric and behavioral health visits, which increased by 42%.

“This means that children and their families are visiting their pediatrician less throughout the year, presumably resulting in fewer opportunities for the pediatrician to connect with families on preventive care and healthy behaviors, like vaccinations and good nutrition,” said Ray, also a pediatrician and director of health system improvements at UPMC Children’s Community Pediatrics. “The question is: Why? We don’t have the definitive answer, but our data give us some clues.”

Pediatric primary care visits declining

One possible explanation is that children are getting care elsewhere. Visits to urgent care, retail clinics and telemedicine consults for problem-based care increased during the study period. But that increase accounted for only about half of the decrease in visits to primary care pediatricians.

Higher out-of-pocket costs probably also explain why some parents aren’t taking their children to the pediatrician for medical concerns, Ray said. During the time period studied, out-of-pocket costs for problem-based visits increased 42%, while inflation-adjusted median household income rose by only 5%. Previous studies have found that even $1-$10 increases in copayments are associated with fewer visits.

Other factors also could be at play, the research team noted. With more parents working, some may find it difficult to bring children in for care. And there may be less need for some visits. Vaccination has dramatically reduced rates of ear infections and hospitalizations. Pediatricians are being more careful with prescribing antibiotics, and this could be causing parents to watch children with cold symptoms for longer before seeking care. Recent research showing that children with ear or urinary tract infections do not always need to come back for rechecks also may have cut down on the number of visits for problems. And parents have ever-increasing amounts of information available to them online as they are deciding whether to seek care.

The drop in visits is not isolated to children. “This decline among children is echoed in other studies among younger and older adults,” added senior author Ateev Mehrotra, MD, MPH, associate professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School. “Due to a variety of forces, Americans are not as connected with their primary care providers.”

Additional authors on this research are Zhuo Shi, BA, of Harvard University; Ishani Ganguli, MD, MPH, and E. John Orav, PhD, both of Harvard University and Brigham and Women’s Hospital; and Aarti Rao, BA, of Mount Sinai.

This research was funded by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant K23HD088642 and gifts from Melvin Hall.